As witness Step On It, his new album of jazz standards, he’s a distinctive interpreter of songs, and a master of the trio format. This is his third topnotch outing with bassist Bob Cranshaw, best known for his long association with Sonny Rollins, and the prolific drummer Lewis Nash, who backed Gillespie on his final recordings.

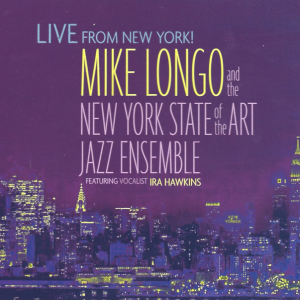

Longo’s gifts as a composer are highlighted on Live from New York, the latest album by his 17-piece New York State of the Art Jazz Ensemble. Recorded at the John Birks Gillespie Auditorium in the New York City Baha’i Center (Longo is a member of the Baha’i faith, as was Dizzy), it includes three distinctive originals.

And then there’s the six-man Mike Longo Funk Band. Its new live album, Jazz Meets Funk, available through the pianist’s Jazzbeat.com web site, reawakens the ’70s jazz-rock with which he burnished his reputation on electric piano. Long out of print in this country, The Awakening (featuring James Moody, Virgil Jones, Curtis Fuller—and Gillespie on congas) and 900 Shares of the Blues (featuring Joe Farrell and Randy Brecker) are regarded as “stone” classics by a new generation of groove heads.

“My lead alto player got me to pull out the charts from those records and we played them in concert in 2008,” Longo said. “The music went over really well. Kids are catching on to me as a ‘cult classic’!”

As winning as he is in expanded settings, he’s at the height of his creative powers leading a trio. Playing songs you’ve heard hundreds of times, he makes you think you’re hearing them for the first time. Wayne Shorter’s “Nefertiti,” a pensive modal classic by the Miles Davis Quintet, is transformed on Step On It into what Longo called “a real groove thing.” Joe Henderson’s mini-tone poem, “Black Narcissus,” is pumped with energy. “We play it like a delicate waltz,” said the pianist. His polymetric threesome’s treatment of “Poinciana” was influenced not by Ahmad Jamal’s classic cocktail recording but the Four Freshmen’s textured, high-spirited rendition.

“Jazz is like a baseball game,” said Longo. “People say, oh man, I’ve seen all this before. But then you start playing, even with the least bit of preparation, and you find something new in the themes, the time conception, the band’s touch. The three of us all come from the same school of playing, and it’s the same with my other trio [featuring bassist Paul West and drummer Ray Mosca, with whom he recorded the terrific live 2012 album, A Celebration of Diz and Miles]. We don’t know what’s gonna happen.”

Michael Joseph Longo was born on March 19, 1939 in Cincinnati. He started playing the piano at age 3, and his family moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, when he was 8. His father, who had a produce business, played bass in a weekend jazz band to earn extra money. His mother played piano in church. His sister was a tap dancer.

Among the pieces of music he heard as a child, none was more significant than the soundtrack to “Little Toot,” a 1948 cartoon featuring the Freddy Martin Orchestra. Young Mike memorized the rollicking left-hand patterns of pianist Jack Fina and put together his own version of the tune, a takeoff on Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumblebee.”

“That’s when my mother took over,” said Longo. “She bought me the real music to play.” After he won first prize in a talent contest at the age of 12, his loyalties, which had been divided between music and baseball, tilted definitively toward the former.

One major turning point for him came when Cannonball Adderley, then the band director at a Fort Lauderdale high school, sent out word that the woman who played piano at a local sanctifying church had died and they needed a replacement. Longo answered the call on his own band director’s recommendation.

After meeting and playing with Cannonball at a jam session a couple of months later, and telling his father how floored he was by the still unknown alto saxophonist, his father hired Adderley for some gigs. In return, Adderley got Longo fils a job playing R&B with him on the chitlin circuit, in a band nominally led by one Harold Ferguson.

Another early pivotal moment for Longo was a Jazz at the Philharmonic concert in Fort Lauderdale. Knocked out by the playing of featured pianist Oscar Peterson, he bought all of the Peterson records he could with money from his paper route. “I was hooked on him,” said Longo, whose relationship with the Canadian great was only beginning.

After acquiring a bachelor’s degree in classical piano from Western Kentucky State University, he played with Glenn Miller alumnus Hal McIntyre’s orchestra, jazz-minded Nashville guitarist Hank Garland, and the Dixieland-style Salt City Six, whose gig at New York’s Metropole Cafe led to a job there for Longo as house pianist. Taken to Chicago for an engagement by storied cornetist Jimmy McPartland, he met Peterson, who was performing at the London House. Beginning in the fall of 1961, for six intensive months in Toronto, Longo took private lessons from the keyboard virtuoso at the Advanced School of Contemporary Music. “I had to practice 13 hours a day,” he said, “but it was worth it.”

Back in New York, he accompanied such singing greats as Jimmy Rushing, Nancy Wilson, and Joe Williams. Serendipity struck at the Metropole, where Longo was performing downstairs with trumpeter Red Allen at the same time Gillespie was leading his band in the room upstairs. During a break, Gillespie saw Longo perform and was impressed enough to name him as one of the best young talents around in the union magazine, International Musician.

Two years later, Gillespie saw Longo perform at Embers East and to the pianist’s great surprise (and amusement) mouthed the words “I love you” at him. Longo was even more surprised months later when Gillespie asked him to become his pianist after seeing Longo’s trio (with bass great Paul Chambers) back Roy Eldridge, a hero of Dizzy’s, at Embers West.

“When I first heard Dizzy and Charlie Parker’s music in the eighth grade, it was like listening to tape running backwards,” said Longo. “But something I heard stuck in my head, a certain sound in Dizzy’s playing. I had this weird dream in which I went to the piano and played that sound like I knew it, the sound of that place in his playing that was falling in a strange place in the time. Everything seemed different to me after that.”

The first night Longo played with Dizzy—Dec. 11, 1966 in Milwaukee—he was in peak form. But the next night, he said, “I took a nose dive.” Gillespie wasn’t happy about it. “I asked him, what, am I supposed to play all out every night? And he said, ‘What the hell am I paying you for?’” That was enough to straighten the young pianist out.

But if they started out in a father-and-son-type relationship, they soon became like brothers. “Dizzy fell in love with my parents and they invited him to stay at our house whenever he wanted, which he did.” (Longo was also very close to James Moody.)

So great was Gillespie’s musical influence—“He wrote left-hand parts that were comparable to Bach inventions”—it was only natural that Longo set higher goals for himself as an artist. His first attempts at composition, he said, were terrible. But a conversation with Benny Carter about the importance of classical composition, and lessons in composing with Hall Overton (famous for scoring Thelonious Monk tunes for orchestra) had him on the right track.

“One of the most important things I learned was discovering the place inside you where real music comes from,” said Longo. “You don’t really compose something, you uncover it. Dizzy used to say music is out there, waiting for someone to come get it.”

Longo’s 1962 debut album, A Jazz Portrait of Funny Girl, was one of numerous jazz-goes-Broadway collections released during that era (Cannonball Adderley’s Fiddler on the Roof followed two years later). In the intervening years, he has amassed a deep body of originals, including a wide assortment written for or about Dizzy, including “Matrix,” “Soul Kiss,” “Samba,” “I Miss You John,” and the orchestral work, A World of Gillespie. He also has enjoyed a successful second career as an educator and creator of instructional books and videos.

Wrote one reviewer, responding to the frequency with which Longo quotes songs in his performances, “They hint at just how much music Longo has running through his veins.” With three different bands and a new generation embracing his work, he’ll continue to have plenty of opportunities to offer more than a hint of his mastery. •